|

| School Reform (M.A. Reilly, 5/2012) |

There's something I've been noticing in some primary classrooms I visit: the children who are struggling the most to acquire alphabetic knowledge, to hear sounds, to remember sight words, or to apply this knowledge to actual reading are often left on their own. You can recognize them easily as they are seated by themselves or when seated with other children they are not attending to whatever is in front of them (a book, a piece of paper). Rather they stare. Or they scribble. Or they leave their seat and crawl on the floor. Now and then you will see them sitting very still almost as if their stillness might be an invisibility cloak. Across time, it seems that if they are propped up behind a book it "counts" as reading. Imagine what these young ones are learning about what it means to read as they sit behind texts they can't decipher and dutifully mimick what the other children do, turning pages and looking--and all the time not understanding or perhaps even knowing that understanding is a goal.

These are the children we (teachers, specialists, principals, superintendents of schools) most need to notice.

II. A Story

|

| Pondering (M.A. Reilly, 2012) |

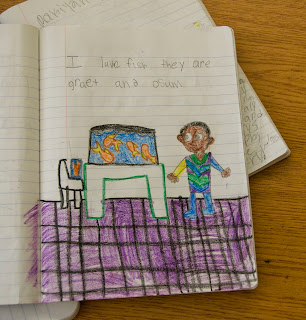

So, we looked and talked about the pictures saying what we thought was happening in each. I then began reading and as I did, I pointed to the words. I invited the child to point and read with me and at first he did not and then he began very, very softly to do so and to point. I lowered my voice as I noticed he was able to read, chiming in at points of difficulty. When we finished the book, the child told me he did not know how to read. I explained that he had just read and did he want to do it again so he could see. He reread the book a second time with very little support and was animated. I happened to have a copy of the book as a flip book and showed it to him. There was space for him to make his own illustrations and he said he would like to do this. So as I taught a reading lesson to a few other children, he sat next to me and illustrated his story. When he was done, I took a look and we discussed the pictures he had made. I then gave him the little book to take home to reread and to add to his home library. I asked his teacher who the child might read the book to in the class and she quickly connected him with another child. The two sat next to each other on the rug and read the story. When I asked the teacher about the child she said he was non-communicative and preferred to sit alone. She told me he did not want to participate.

Encounters like this give me pause. They make me wonder how it is permissible for a child to attend school and not be included, not be overtly taught. How is it we misread such situations? If this was one classroom and one story, it would still be wrong--but it is not an isolated tale. The very children who need the most from us and need it consistently are often the ones who receive the least or when taught are relegated to the teaching assistant instead of the teacher. Is it any wonder that across the country there are children turning 8, 9, 10 and 11 years old who cannot decipher or encode simple sentences. Who among us would not be 'impaired' by such treatment?

III. Counting without Reason

|

| Stopped (M.A. Reilly, 6/2012) |

Sometimes when I talk with principals they want to share student achievement successes their students are experiencing. These stories are grand and important and a pleasure to hear. But the relative success of a school cannot be measured using only a part of the whole. How focused are we on the silent children? The children left alone? The children whose progress appears stalled or perhaps not even started?

I once worked in a district where the number of young people scoring 3 and higher on AP tests was well celebrated by superintendent and the Board, while those not completing high school were less discussed--less visible--even at times rationalized. Practices such as forgetting the very struggling children in order to attend more directly to "those on the cusp" of passing the state test was becoming accepted practice at earlier and earlier grade levels. I know this system is not the only one where such actions are occurring. I have even heard of these practices being touted as test smart practices--of ways to beat the test. The only things "being beaten" are the children we allow to be forgotten, sacrificed. Does this administrative attitude set the stage for the teacher to forget some of the children in the classroom? Does it fuel the belief that there are children who cannot learn? Does it work to undermine our own confidence to teach all?

IV. A Confession of Sorts

Here's what I want you to know though: in every classroom, the child who is struggling can and does make progress as a reader and/or writer when provided a mix of direct instruction and experiential learning that is consistently offered. I don't want to suggest the nature of this work is easy--as it is not. I have found that it helps to have a partner to discuss the theories being formed about the work and the children's learning for this is complex work and as such, the way is nomadic. There is no finished map someone can give you, common core included, although there are other journeys you can study if so inclined.

The made journey with others offers the most significant possibilities for deep learning.

The drive to make sense of the struggle and to build a bridge between what children know and need to know is powerful, demanding and enticing. We are bound to make errors, lose our way, and regroup. We will be imperfect. But know this: It is this drive that education reform must produce and nurture. Everything else misses the proverbial mark.

.JPG)